INFORMATION

| Born In : | Bila Tserkva, Ukraine |

(May 9, 1882 – June 19, 1933)

To better understand what made Yossele Rosenblat “Yossele” take a moment to absorb the following quote; “I think he’s singing pure spiritual, he’s making the sound of what he’s experiencing as a human being, turning it into the quality of his voice, and what he’s singing to is what he’s singing about. We hear it as ‘how he’s singing.’ But he’s singing about something… it doesn’t sound like it’s going up and down (conventional melodic progression) it sounds like it’s going out. Which means it’s coming from his soul.”

What makes the preceding “review” even more impressive than it’s unerringly accurate insight, is the fact it was said by jazz legend Ornette Coleman, during a 2006 interview with Ben Ratliff a NY Times music reviewer. Mr. Ratliff began the interview by asking Mr. Coleman—one of the jazz world’s most revered saxophonists– to choose different albums that “spoke to him”. When asked how Coleman who was born in 1930’s Chicago knew about Yossele Rosenblatt, Coleman replied ““I was once in Chicago, about 20-some years ago, a young man said, ‘I’d like you to come by so I can play something for you.’ I went down to his basement and he put on Josef Rosenblatt, and I started crying like a baby. The record he had was crying, singing and praying, all in the same breath. I said, wait a minute. You can’t find those notes. Those are not ‘notes.’ They don’t exist.

Proof positive that music is truly the universal language—especially when that music is being created by Yossele Rosenblatt

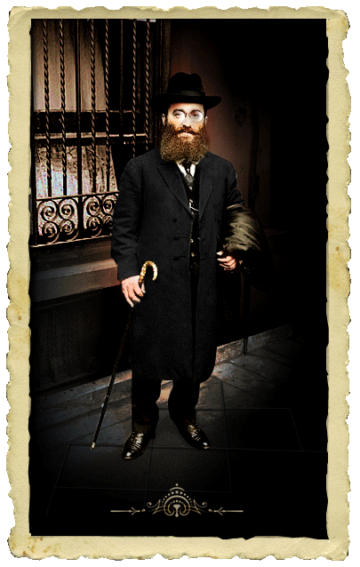

Rosenblatt was born in 1882 in a small Ukrainian town, in a house with a dirt floor. By the 1920s, he was the preeminent Chazzan in the United States (and according to many the world) and was often referenced together with opera great Enrico Caruso. Reviewers sometimes described Rosenblatt as a man with two, even three voices: a warm baritone, a ringing tenor, and a shimmering falsetto. What’s more, he could move between them with ease.

Recognized early on as a prodigy, Rosenblatt was just 8 years old, when he began performing in some of the most prestigious shuls in Europe. While he immigrated to New York in 1912, his reputation preceded him which resulted in his appearances being “Standing Room Only” (and not just during Kedusha). Unlike most chazzanim of the era, Rosenblatt often composed his own tunes for various tefillos rather than opt for the more “free form” almost improvisational style favored by most all other chazzanim. When asked why he did this, he said that by connecting the davening with “fixed” melodies (rather than “on the spot” improvised ones) it became easier for his kehillos to follow. Clearly, Rosenblatt wasn’t about davening as a solo performance—like the opera or theater, to him it was a “group” dialogue with G-d and he felt he had to do everything in his power to facilitate this.

Unlike many of his contemporaries who provided their services to the highest bidder—regardless if that bidder was Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, or a concert promoter, Rosenblatt’s unique messikus came from “living “the davening—not merely “performing” it. Case in point, in the 1920’s he partnered with “Mr.” Shraga Feivel Mendelovitz in founding the Jewish Light (Dos Yiddishe Licht) newspaper. The purpose of the publication was to give the largely secular Jewish population a torah-true alternative to The Forward, The Workmen’s Circle/Bund, and other publications of the era that were focused on turning Judaism into a culture rather than a religion. While the venture was a commercial failure, the success of publications like Hamodia, Mishpacha and The Jewish Press attest to the fact that it was simply ahead of its time

Thanks to an extensive recording and chazzanus career, he was courted by some of the world’s leading opera houses and turned down highly lucrative offers—including one in 1918 which would have paid him $1000 a night—the equivalent of almost $16,000 a night in today’s dollars! Rather than isolate him, this only made him more popular as people wanted to “experience” the Chazzan whose values were not for sale, no matter the price.

Not surprisingly, the fledging film industry also came calling and while Rosenblatt turned down $100,000 to play a part in the first “talking” picture called ‘The Jazz Singer’ (the story of a Chazaan who does succumb to the temptations of ‘stardom”), he held his ground and ultimately got the powerful heads of Warner Brothers (as in the actual Warner Brothers) to work with him on his terms (something unheard of in that era) and ended up in the film appearing as himself in concert.

As stellar as his career and reputation were, they couldn’t save him from the economic ravages of The Great Depression. To make ends meet, he accepted a project that required him to record the music for a documentary in Eretz Yisroel where he died of a heart attack in 1933.

While the uninitiated regularly describe him as having elevated the “Cantorial Arts”, it’s ironic that few have described his uniqueness as eloquently as Mr. Coleman.